COPING UNDER QUARANTINE

COVID-19 IS WREAKING HAVOC ON MORE THAN JUST THE PHYSICAL BODY.

Text & Photos By Gabby Miller

I didn’t adjust well to New York City shutting down, and I noticed that many of those around me weren’t adjusting well either, especially for those with mental health issues, myself included. It felt like it happened over night. On a Friday night in early March, I was at a bar drinking with friends to celebrate being done with our master’s projects, and only a week later, the lights of almost every business on my normally-bustling block were indefinitely switched off. As we retreated into self-isolation, degrees of loneliness began to sink in. Yet, we’re not alone in our experiences, and this project seeks to provide a small lens into a spectrum of experiences that the pandemic has created in an attempt to connect with one another through empathy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us all to reckon with the social fabric of our society and in what ways technology both helps and hurts interpersonal connectivity. Classes and office meetings have moved to zoom. Doctors have adopted Telehealth services to see many of their patients. And being with each other while not actually being with each other, is collectively traumatizing those of us isolating in the midst of the unknown. That’s according to Jill Zalayet, doctor of social work and licensed psychoanalyst who specializes in the treatment of trauma.

Zalayet says that the pandemic is producing increased feelings of vulnerability and anxiety for everyone. “Anxiety is generally a byproduct of feeling unsafe, and so when you match that with an unsafe world and a precarious sense of internal safety, there’s a lot of anticipatory anxiety around what’s going to happen,” said Zalayet.

For people with pre-existing mental health issues, though, Zalayet says the pandemic is exacerbating vulnerabilities and retriggering traumas that they’d maybe previously resolved or worked through. “The toll that this takes emotionally, is greater than some people can even really acknowledge and there's a cumulative exhaustion.”

It’s urgent to document what’s happening around us, but fighting against an invisible enemy has made that especially challenging for visual storytellers, who have traditionally relied on being physically close to their work and the people in it. This project interrogates what it means to create a picture. Do photojournalists have to physically click the shutter button for their documentation to be seen as a legitimate form of reporting? Who gets credit for what role without creating hierarchies of importance? And can journalists attribute this work to themselves? In many ways it boils down to who can claim ownership over an image, and what one believes a photojournalist's role is. Are we taking pictures or creating images with our subjects, virtually or not? This ongoing conversation has once again been thrust under the spotlight as this virus ravages through the minds and bodies of people around the world.

CELINA MCCARTHY

25-year-old Brooklyn resident, Celina McCarthy, is self-isolating at her girlfriend’s apartment. The day we spoke, she recounted waking up, making smiley face chocolate chip pancakes with bacon, and sitting on the rooftop to catch some sun. That day was windy and cold, though, and instead of grabbing food at the deli like she’d planned, she walked out with only orange juice and Prosecco. She also took a nap, something she never does.

“I was sleepy out of nowhere. I'm so unbelievably bored and tired of seeking fulfillment from people who are also bored.”

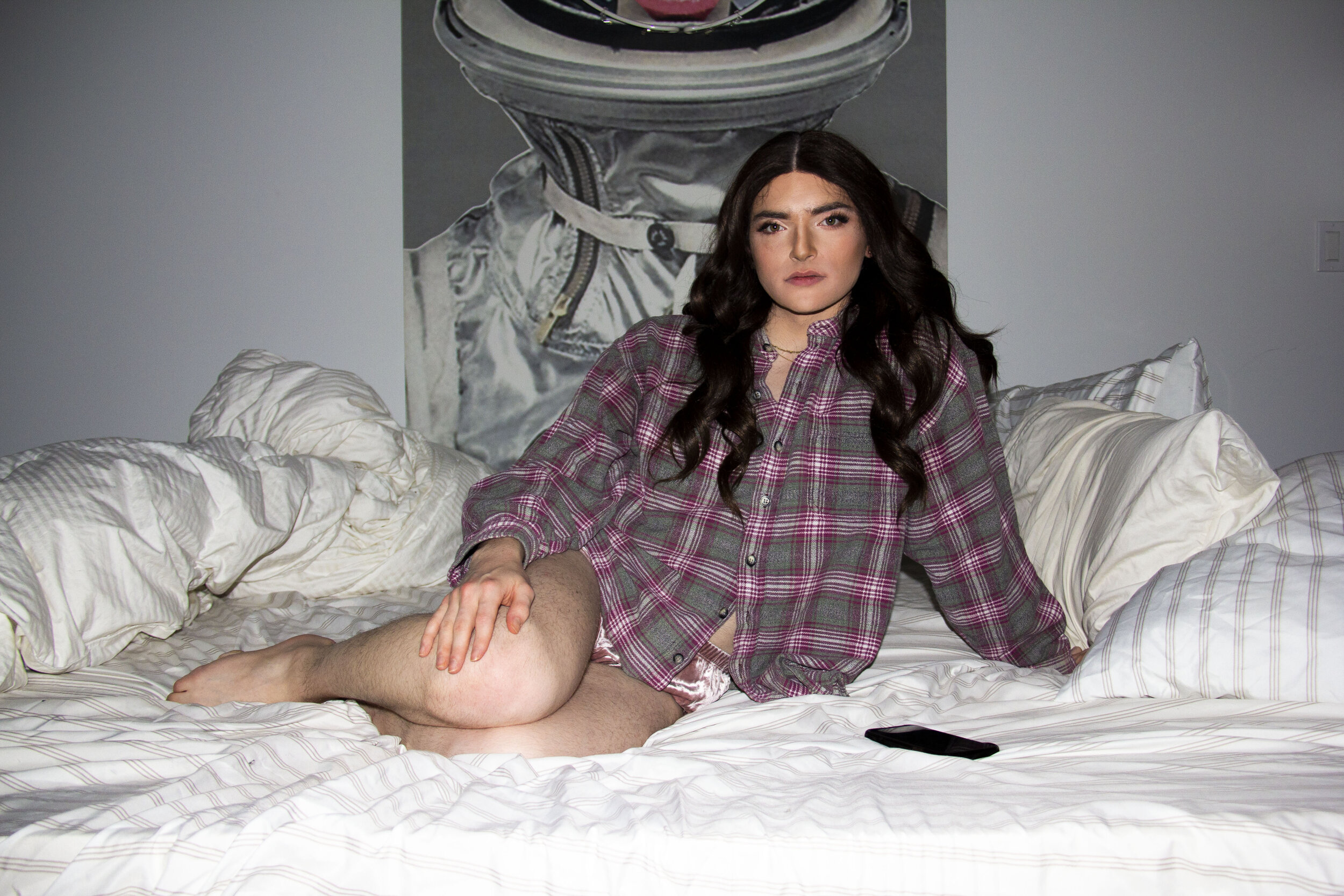

Left: Celina and her girlfriend spend a Sunday morning in bed. Right: Celina adds a smiley face to her pancakes with chocolate chips.

Like many in self-isolation, living with her girlfriend has been helping Celina stay sane, especially as someone with anxiety. “I would be losing my mind completely. I'd be becoming a hermit in my apartment. Like, not moving around, sulking, crying,” she explained.

For a bit of respite from her surroundings, Celina sometimes takes her comforter, pulls it over her head like a tent, and blasts music really loudly from her laptop. “I’m so tired of this apartment and not being able to experience any other type of social or environmental stimulation,” she explained.

“I close my eyes and I come out [the comforter] feeling like I’ve been somewhere else.”

Celina McCarthy looks at her computer screen from the comfort of her duvet. “I close my eyes and I come out [the comforter] feeling like I’ve been somewhere else.”

On the morning of Wednesday, May 6, Celina woke up to an email notifying her of mass layoffs at Uber. Then, she was sent a Zoom link where a crying woman from management delivered the news that Celina and several others were being laid off from their jobs at Uber's New York City headquarters in Queens. “I feel like it was random,” said Celina over text message. A mom with three kids, two of her supervisors, all-stars in other departments were just some of her colleagues let go for reasons that she can't make sense of.

"The way they did it prevented me from having any sense of closure because they did it in such an impersonal and cold way," said Celina. "It would've been nice to get a 'thanks for all the stuff you did' because I worked there for three years."

But fortunately for Celina, she got a good severance package and had been looking for a reason to leave the company after spending years unhappy there. She said, "It wasn't good timing with coronavirus, but it was good otherwise."

GEEP WARHAFTIG

Brooklyn-based art director Geep Warhaftig has been holed up in a close friend’s apartment throughout quarantine. She found the first few weeks of quarantine easy to manage by keeping busy with work and doing at-home workouts with her roommate. Then the work dried up and she lost her freelance income.

"I hated my job but I was working, and that preoccupied a lot of my headspace because it gave me an excuse to not be like this productive magic person that everyone's trying to be right now," she explained.

Geep Warhaftig applies a full face of make-up despite being confined to the apartment where she's staying.

Geep says she's very aware of the variables that play into her mood since she's been doing psychoanalytic therapy for over two years now. "I can feel my lows getting lower, and I can feel my highs not reaching a level of high that they should be."

That's also how she knew that the general loss of control she felt over her body and her mental health was directly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I already have very bad body dysphoria because of, you know, the whole trans thing, but it's been getting amplified,” explained Geep. Getting ready with nowhere to physically go, though, has been an act of reclaiming her circumstances: “It’s for myself.”

Geep Warhaftig takes a portrait of herself in bed after doing her hair and make-up in quarantine.

Geep's roommate helped capture these images, but they were mainly created and directed by Geep. There was also a remote pre-planning discussion via Zoom between Geep and I about visualizing what they had relayed to me regarding their experiences in quarantine.

Creating these images was a challenge for her because her photography focuses on capturing others’ intimate, candid moments. “I never, ever photograph myself to be honest,” said Geep. She also explained that any photos she posts on social media are retouched. “I do in Photoshop what I would like to surgically get done, so I did that to these photos too, to alleviate the body dysphoria and make me feel a little bit better.”

Geep talked a lot about escapism via technology, such as getting lost in her phone on apps like Grindr or attending Zoom parties on her computer. “There was one night where I did three Zoom parties in one day,” recounted Geep. “They’re really draining, so much that they’ve become not fun sometimes.”

Geep gets lost in her phone while lying in bed.

An hour after our conversation, though, Geep had another virtual date scheduled with a guy she started talking to right before New York City went on “pause” and changed life as we once knew it. "I have no idea where our relationship is, but we've gone on a Zoom date every week of quarantine and FaceTime for an hour or two almost every week, so those have been nice."

KATHRYN MARSHALL

Kathryn Marshall moved from San Francisco, California to Portland, Oregon right before COVID-19 began sweeping across the United States. Only two weeks into starting her new job there, the office closed down, and she began working remotely. Then the layoffs started happening around her and she now does the work of four people while living with the fear of losing her job next.

“I work on an account where theoretically my salary is paid for by a one year contract, so I may not have to worry until the end of the year,” explained Kathryn. “But I’ve seen some crazy shit. The layoffs that I’ve seen not just at my company, but in general, don’t make sense.”

She’s lost her job in the past due to mental health issues. And exactly two years before quarantine, she was in a full-time outpatient program for substance abuse and an eating disorder. “Being able to be stable and maintain a certain level of productivity is something I’m very stressed about and think about a lot,” said Kathryn.

It’s been easier for her to deal with managing her sobriety during self-isolation than food has been. “You need to eat everyday, you need to figure out a plan of attack for food and some level of physical movement,” she said. Between working long hours at home and sitting at her desk all day, it’s hard not to obsess over food.

Kathryn’s been getting back into Soundcloud lately (she used to mix music in college) and has been spending a lot of time on social media apps like Twitter and Instagram—a double-edged sword. “Time management wise, it’s been really difficult to find time for self-keeping or self-maintenance,” she said. Relying on social media doesn’t require her to do anything outside of her everyday activity, like picking up a guitar would, so it’s an easy way to cope.

From an outsider's perspective, Kathryn’s social media presence is entertaining. She seems to have fun with it too, posting screenshots of absurd conversations with random men from dating apps or texts that “explain” why she was ghosted (which she then made into a custom t-shirt pictured below).

Being active on social media right now gives her two types of validation. “I use it to literally speak to people, and potentially pursue things romantically,” Kathryn said. “Not like dating stuff because I can't right now but I just do it for the shits and giggles. I think it's pretty funny.”

However, the largest percentage of her time spent online is for social validation. “I'm alone, so I have nothing else to do.”

Kathryn made a shirt during self-isolation of a text message she received from a guy who ghosted her.

Lurking beneath the surface of those posts, though, is something much more complex. “As much fun as I have putting up those men on the internet and as much as I think I’m building an entertaining story for other people, I think there’s still really deep rooted insecurities that I have in regards to my romantic relationships,” explained Kathryn. And those insecurities can get so overwhelming that even a slight wind can knock her over, especially in self-isolation.

What’s getting her through the pandemic is maintaining some sense of normalcy. “I know that everyone is dealing with the same thing right now, but no one is dealing with the same thing right now.” Normalcy for her means continuing to find funny content to put on the internet. “And that’s not funny, that fucking sucks.”

Kathryn often looks outside at her neighbor's chicken when she can't focus during work meetings.

ELIZABETH ARCADIA

Elizabeth moved to Washington, D.C. after college hoping to work on Capitol Hill, but changed her mind and decided she wants to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree in poetry instead. While applying for programs, she was working at Lost City Bookstores—until the pandemic hit, the bookstore closed indefinitely, and Elizabeth got laid off.

She was already going through a hard time prior to COVID-19. Last October, she had to drop down to part time hours at the bookstore while in a full-time outpatient treatment program. And now in self-isolation, her relationship to her mental health remains complicated. “My anxiety and depression is definitely way worse,” said Elizabeth. “But on the other hand, since I'm not out in the world and exposed to anything outside of my room, I'm not getting my PTSD symptoms triggered much.”

It’s hard for Elizabeth to get out of bed, and even harder to leave her room because she doesn’t get along well with her roommates. She’s grateful for her two cats, though, who she wakes up to feed around noon before falling back asleep until around 3 p.m. each day. “My cats are something that during the day lifts my mood, just interacting with them, singing to them,” said Elizabeth.

Left: Elizabeth opened her Nintendo Switch to find that the last time it was on, her and her boyfriend were playing a game together. Right: Elizabeth's cat, The Fox, sits atop her shoulder.

Food has also been a major source of anxiety for Elizabeth during the pandemic—both shopping for and eating it. At the grocery store, feelings of guilt about how much money she’s spending as well as how much food she’s buying surface. “I’ll look at my cart and be like, this is way too much food, I can’t possibly need all of this, I don’t deserve this. I’m using my dad’s money to pay for it, I should feel bad about it,” she described.

She feels lucky that her boyfriend has been around to help her get through grocery shopping trips (they're self-isolating separately). The last two resulted in panic attacks, and he was there to check out and pay while Elizabeth went and waited in the car, trying to calm down.

The rough draft of a poem Elizabeth has been working on while in quarantine.

Being confined to her small apartment has Elizabeth thinking a lot about the outdoors. “I miss hiking so badly,” she said. “The thing is, it isn't actually something I'll do once quarantine is over because I don't have a car. But it's something I think about a lot.”

GABBY MILLER

For as long as I can remember, I’ve used my bed as a refuge. It’s been my dinner table when I lived in a house with people I didn’t know and a city I didn’t like. It was where I spent an entire winter break alone one year of college—depressed, and eventually hospitalized for it.

Quarantine has been no different. As my mental health began to slip, I turned to teary phone calls with my mother in bed and taking what I call “depression naps,” or naps I use as an emotional reset when I begin to lose grasp of my emotions. Sometimes it works, other times not so much. Taking these self-portraits in my bed wasn't a conscious decision, it just wouldn't have made sense to take them anywhere else.

Then the big break down came. A bad reaction to new medication led to a different mental health diagnosis and virtual therapy. And for the first time in my life, I think I’m going through a break up with my bed, or at least a break, for now.

On nights that I couldn’t sleep comfortably with my partner, Eliza, I’d quietly tiptoe into my roommate’s empty bed (she’s quarantining in California) and get the rest my bed suddenly wouldn’t provide. Then it became my regular nap spot, thanks in part to the dark alleyway it faces, making it the perfect daytime den.

But when I finally uprooted my whole night’s sleep and brought Eliza and our blankets into the other bed in the middle of the night, that was when I knew something had changed.

The author and her girlfriend, Eliza Loukou, comfort one another in her bed.

I used to spend every day looking forward to going home and drifting to sleep under my covers, napping away the exhaustion that had been gnawing at me, usually from a desk. Now I can’t even stand the feeling of my own comforter against my skin. How soft the mattress is. Even the rug on the side of the bed has become unpleasant to step on.

My problems at the beginning of quarantine used to stem from a lack of visual stimulation, staring at the same walls and the same plants and the same furniture and the same reflection in the mirror day after day. But now the isolation has crept into other sensations, and with it, I’ve begun to loathe my own bed.

But Eliza comes with me, always. Quarantine has made visible some of the worst parts of myself, and with another person to witness every drastic mood shift, every dark day, every flashback that leads to suddenly bursting into tears, it’s stressful.

Yet somehow, she still holds me in whatever bed I need that night and even if tomorrow is the same as it was yesterday during quarantine, sometimes that consistency is just what I need.

Reporter's Notes:

Each of these visualization processes was unique and collaborative, albeit remote and virtual. It was also an intimate experience done through a computer screen, as the people who were featured (some were strangers, others were friends) shared with me detailed accounts over many hours about what they were going through physically and psychologically.

At times I acted as photo editor, sifting through the hundreds of iCloud images Elizabeth took of herself or going back and forth with Geep to narrow down the 30 original selects she was comfortable using. However, I maintained full decision-making power over which images would be published out of the options they had sent me. This was especially important because the images needed to correspond with the text, which was born out of the interviews I did with each person.

Other times I felt more like a creative directive, like with Celina's images. When she told me about the "tent" she made as an escape from her apartment, I knew that would be visually central to her story. After a few failed self-portrait attempts from both in and outside an enclosed version of it, I had the idea to let the viewers into the tent by constructing a vertical cross-section of it. Her girlfriend used her iPhone 11 to create this portrait, incorporating a sketch of what I envisioned this looking like while making their own decisions about color and composition. Contrastingly, the image of the feet was something I saw posted on Beca's Instagram (used with their permission) and I had no role in its making.

![Celina McCarthy looks at her computer screen from the comfort of her duvet. “I close my eyes and I come out [the comforter] feeling like I’ve been somewhere else.”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eb08fd0cfabd23e14ab62bb/1588782766395-5468XMVF202U5S41AMGL/Celina-Tent.jpeg)